In previous sections we considered the relationships between agent and principal. Now we turn to relationships between third parties and the principal or agent. When the agent makes a contract for his principal or commits a tort in the course of his work, is the principal liable? What is the responsibility of the agent for torts committed and contracts entered into on behalf of his principal? How may the relationship be terminated so that the principal or agent will no longer have responsibility toward or liability for the acts of the other?

Principal’s Contract Liability Requires That Agent Had Authority

The key to determining whether a principal is liable for contracts made by his agent is authority: was the agent authorized to negotiate the agreement and close the deal? Obviously, it would not be sensible to hold a contractor liable to pay for a whole load of lumber merely because a stranger wandered into the lumberyard saying, “I’m an agent for ABC Contractors; charge this to their account.” To be liable, the principal must have authorized the agent in some manner to act in his behalf, and that authorization must be communicated to the third party by the principal.

Principal’s Tort Liability

Direct Liability

There is a distinction between torts prompted by the principal himself and torts of which the principal was innocent. If the principal directed the agent to commit a tort or knew that the consequences of the agent’s carrying out his instructions would bring harm to someone, the principal is liable. This is an application of the general common-law principle that one cannot escape liability by delegating an unlawful act to another.

The syndicate that hires a hitman is as culpable of murder as the man who pulls the trigger. Similarly, a principal who is negligent in his use of agents will be held liable for their negligence. This rule comes into play when the principal fails to supervise employees adequately, gives faulty directions, or hires incompetent or unsuitable people for a particular job. Imposing liability on the principal in these cases is readily justifiable since it is the principal’s own conduct that is the underlying fault; the principal here is directly liable.

Vicarious Liability

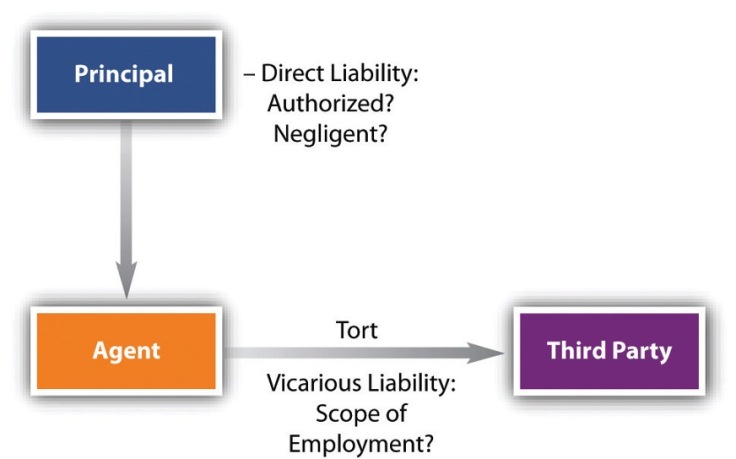

But the principle of liability for one’s agent is much broader, extending to acts of which the principal had no knowledge, that he had no intention to commit nor involvement in, and that he may in fact have expressly prohibited the agent from engaging in. See Baltimore Police Dept. v. Cherkes, 140 Md. App. 282, 780 A.2d 410 (2001). This is the principle of respondeat superior(“let the master answer”) or the master-servant doctrine, which imposes on the principal vicarious liability (vicarious means “indirectly, as, by, or through a substitute”) under which the principal is responsible for acts committed by the agent within the scope of the employment (see Figure 20 Principal’s Tort Liability).

Figure 22 Principal’s Tort Liability

The modern basis for vicarious liability is sometimes termed the “deep pocket” theory: the principal (usually a corporation) has deeper pockets than the agent, meaning that it has the wherewithal to pay for the injuries traceable one way or another to events it set in motion. A million-dollar industrial accident is within the means of a company or its insurer; it is usually not within the means of the agent—employee—who caused it.

The “deep pocket” of the defendant-company is not always very deep, however. For many small businesses, in fact, the principle of respondeat superior is one of life or death. One example was the closing in San Francisco of the much-beloved Larraburu Brothers Bakery—at the time, the world’s second largest sourdough bread maker. The bakery was held liable for $2 million in damages after one of its delivery trucks injured a six-year-old boy. The bakery’s insurance policy had a limit of $1.25 million, and the bakery could not absorb the excess. The Larraburus had no choice but to cease operations. (See http://www.outsidelands.org/larraburu.php.)

Respondeat superior raises three difficult questions: (1) What type of agents can create tort liability for the principal? (2) Is the principal liable for the agent’s intentional torts? (3) Was the agent acting within the scope of his employment? We will consider these questions in turn.

Agents for Whom Principals Are Vicariously Liable

In general, the broadest liability is imposed on the master in the case of tortious physical conduct by a servant. If the servant acted within the scope of his employment—that is, if the servant’s wrongful conduct occurred while performing his job—the master will be liable to the victim for damages unless, as we have seen, the victim was another employee, in which event the workers’ compensation system will be invoked. Vicarious tort liability is primarily a function of the employment relationship and not agency status.

Ordinarily, an individual or a company is not vicariously liable for the tortious acts of independent contractors. The plumber who rushes to a client’s house to repair a leak and causes a traffic accident does not subject the homeowner to liability. But there are exceptions to the rule. Generally, these exceptions fall into a category of duties that the law deems nondelegable. In some situations, one person is obligated to provide protection to or care for another. The failure to do so results in liability whether or not the harm befell the other because of an independent contractor’s wrongdoing. Thus a homeowner has a duty to ensure that physical conditions in and around the home are not unreasonably dangerous. If the owner hires an independent contracting firm to dig a sewer line and the contractor negligently fails to guard passersby against the danger of falling into an open trench, the homeowner is liable because the duty of care in this instance cannot be delegated. (The contractor is, of course, liable to the homeowner for any damages paid to an injured passerby.)

Liability for Agent’s Intentional Torts

In the nineteenth century, a principal was rarely held liable for intentional wrongdoing by the agent if the principal did not command the act complained of. The thought was that one could never infer authority to commit a willfully wrongful act. Today, liability for intentional torts is imputed to the principal if the agent is acting to further the principal’s business. See the very disturbing Lyon v. Carey, 533 F.2d 649 (Cir. Ct. App. DC 1976). in which the court held the employer (principal) liable for civil damages when employee sexually assaulted customer’s sister during a furniture delivery.

Deviations from Employment

The general rule is that a principal is liable for torts only if the servant committed them “in the scope of employment.” Restat 3d of Agency § 7.07(1). But determining what this means is not easy.

The “Scope of Employment” Problem

It may be clear that the person causing an injury is the agent of another. But a principal cannot be responsible for every act of an agent. If an employee is following the letter of his instructions, it will be easy to determine liability. But suppose an agent deviates in some way from his job. The classic test of liability was set forth in an 1833 English case, Joel v. Morrison. Joel v. Morrison, 6 Carrington & Payne 501 (1833). The plaintiff was run over on a highway by a speeding cart and horse. The driver was the employee of another, and inside was a fellow employee. There was no question that the driver had acted carelessly, but what he and his fellow employee were doing on the road where the plaintiff was injured was disputed. For weeks before and after the accident, the cart had never been driven in the vicinity in which the plaintiff was walking, nor did it have any business there. The suggestion was that the employees might have gone out of their way for their own purposes. As the great English jurist Baron Parke put it, “If the servants, being on their master’s business, took a detour to call upon a friend, the master will be responsible.…But if he was going on a frolic of his own, without being at all on his master’s business, the master will not be liable.” In applying this test, the court held the employer liable.

The test is thus one of degree, and it is not always easy to decide when a detour has become so great as to be transformed into a frolic. For a time, a rather mechanical rule was invoked to aid in making the decision. The courts looked to the servant’s purposes in “detouring.” If the servant’s mind was fixed on accomplishing his own purposes, then the detour was held to be outside the scope of employment; hence the tort was not imputed to the master. But if the servant also intended to accomplish his master’s purposes during his departure from the letter of his assignment, or if he committed the wrong while returning to his master’s task after the completion of his frolic, then the tort was held to be within the scope of employment. “An employee acts within the scope of employment when performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control. An employee’s act is not within the scope of employment when it occurs within an independent course of conduct not intended by the employee to serve any purpose of the employer.” Restat 3d of Agency, § 7.07.

This test is not always easy to apply. If a hungry deliveryman stops at a restaurant outside the normal lunch hour, intending to continue to his next delivery after eating, he is within the scope of employment. But suppose he decides to take the truck home that evening, in violation of rules, in order to get an early start the next morning. Suppose he decides to stop by the beach, which is far away from his route. Does it make a difference if the employer knows that his deliverymen do this? It depends.

The Zone of Risk Test

Court decisions in the last forty years have moved toward a different standard, one that looks to the foreseeability of the agent’s conduct. By this standard, an employer may be held liable for his employee’s conduct even when devoted entirely to the employee’s own purposes, as long as it was foreseeable that the agent might act as he did. This is the “zone of risk” test. The employer will be within the zone of risk for vicarious liability if the employee is where she is supposed to be, doing—more or less—what she is supposed to be doing, and the incident arose from the employee’s pursuit of the employer’s interest (again, more or less). That is, the employer is within the zone of risk if the servant is in the place within which, if the master were to send out a search party to find a missing employee, it would be reasonable to look. See Cockrell v. Pearl River Valley Water Supply Dist., 865 So. 2d 357 (Miss. 2004).

Other Torts Governed by Statute or Regulation

There are certain types of conduct that statutes or regulation attempt to control by placing the burden of liability on those presumably in a position to prevent the unwanted conduct. An example is the “Dramshop Act,” which in many states (about 22) subject the owner of a bar to liability if the bar continues to serve an intoxicated patron who later is involved in an accident while intoxicated. As noted, not all states have Dramshop Acts (only about 22); Maryland does not. See Warr v. JMGM Group, LLC, 433 Md. 170, 70 A.3d 347 (2013). Another example involves the sale of adulterated or short-weight foodstuffs: the employer of one who sells such may be liable, even if the employer did not know of the sales.

Principal’s Criminal Liability

As a general proposition, a principal will not be held liable for an agent’s unauthorized criminal acts if the crimes are those requiring specific intent. Thus a department store proprietor who tells his chief buyer to get the “best deal possible” on next fall’s fashions is not liable if the buyer steals clothes from the manufacturer. A principal will, however, be liable if the principal directed, approved, or participated in the crime. Cases here involve, for example, a corporate principal’s liability for agents’ activity in antitrust violations—price-fixing is one such violation.

There is a narrow exception to the broad policy of immunity. Courts have ruled that under certain regulatory statutes and regulations, an agent’s criminality may be imputed to the principal, just as civil liability is imputed under Dramshop Acts. These include pure food and drug acts, speeding ordinances, building regulations, child labor rules, and minimum wage and maximum hour legislation. Misdemeanor criminal liability may be imposed upon corporations and individual employees for the sale or shipment of adulterated food in interstate commerce, notwithstanding the fact that the defendant may have had no actual knowledge that the food was adulterated at the time the sale or shipment was made.

Attribution and licensing: Business and the Legal Environment. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Anonymous. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/business-and-the-legal-environment/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/buslegalenv/